Though much of his life has been documented for posterity, a number of gaps still exist in the collective record of his life and times.

One would just naturally anticipate that a person as “celebrated” as is John Henry Holliday would have little unknown information in the story of his life – even with a man as secretive about his personal life as was he. Holliday, however, seems to be the exception to the rule, as is the case concerning a number of aspects of his life. Many have speculated and offered supposition regarding these “unrecorded” and therefore unknown details, and therein lies much of the intrigue of this famed Old West figure from Georgia.

The Swimming Hole Incident

Much has been made over the years of a presumed “incident” between John Henry Holliday and several Blacks at whom he supposedly directed gunfire in an argument over a favored “swimming hole” at some point in his youth. Just as with many circumstances which make a grand story if one is able to “reinvent” them into an event involving a racial component, this one also has been blown out of proportion if not completely misrepresented. It just naturally makes the story and character that much more controversial if “the race card” can be played.

First of all, much of the knowledge of this presumed “incident” was initially presented as fact by John Henry’s cousin, Mrs. Clyde McKey White, and subsequently repeated by William Barclay “Bat” Masterson, Walter Noble Burns and others. While not denying that such an “incident” may, in fact, have actually occurred, the individuals making this contention either used faulty information, or were simply unreliable as sources – or both.

Mrs. McKey’s “Papa told me. . .” account regarding Doc and the incident appears highly unlikely when examined in the light of day. “Papa” quite likely told his daughter many things, but that doesn’t necessarily make them true, and Mrs. McKey simply was not present herself to witness whatever incident actually occurred, so she could only repeat what she “thought” her father had stated scores of years earlier. This isn’t exactly the concept upon which “factual information” is based.

And by the time “Bat” Masterson got around to repeating what was little more than a rumor from Mrs. McKey, he (Bat) was little more than a derelict alcoholic who had earlier disgraced himself in towns in the West such as Denver, Colorado, to the point of being permanently ejected and barred from those municipalities. Having retired to the New York City offices of the Morning Telegraph newspaper, Masterson had been forced to support himself with inflated “remembrances” of his days in the West and the famed gunmen with whom he had interacted.

In May of 1907, Masterson produced an article for publication in Human Life which introduced many readers to the presumed swimming hole incident involving Holliday. Master Bat had little evidence other than the rumor-mill to support his contention about Holliday and a matter as serious as murder. “The indiscriminate killing of some Negroes in the little Georgia village in which he lived was what first caused him (Holliday) to leave his home,” Masterson wrote. “The trouble came about in rather an unexpected manner one Sunday afternoon – unexpected so far, at least as the Negroes were concerned.”

The article Masterson penned for Human Life can only be described today as a critically unfair fabrication regarding Holliday which unjustly became a portion of the Georgian’s permanent record. Masterson’s dislike for Holliday is well-known, resulting mainly from a distaste for the Georgian’s quick temper and periodic alcoholic rages. Bat Masterson had no proof whatsoever to back up his contention.

In retrospect, this incident could have involved Blacks. It could also have, to the contrary, involved only Whites. Holliday’s actions – if they occurred at all – could easily also have been justifiable, but it makes a much more dynamic story if it can be conveyed in a dramatic racial context.

First of all, this supposed racial incident which was published in Masterson’s fourth installment of his “Famous Gunfighters of the Western Frontier” series supposedly occurred after the Holliday family had relocated to “Valdosta,” Georgia, to escape the onslaught of Gen. William T. Sherman’s troops through Georgia in the final year of the U.S. Civil War. Masterson, avoiding specifics for understandable reasons, stated it occurred “near the little town in which Holliday was raised. . .”

Repeating the rumor in 1927, Walter Noble Burns in his Tombstone: An Iliad of the Southwest was the first to specifically establish Valdosta and the Withlacoochee River in that vicinity as the site of the incident. The “respected writer,” William Barclay Masterson, had stated that it occurred in “the little town in which Holliday was raised,” so Burns immediately reasoned that Masterson had to be referring to Valdosta/Lowndes County and the Withlacoochee. But is this accurate?

Since there were no other swimming holes – as it were – which John Henry might have conveniently frequented in the vicinity of his home in Lowndes County except along the section of the Withlacoochee River flowing through his McKey uncles’ property (which adjoined the Holliday property), and with the logistical requirements of physical travel being what they were in the 1870s, logic would dictate that a popular swimming spot frequented by the McKey and Holliday boys would not have existed anywhere except upon the McKey property. The Holliday property had no swimming holes.

And from whence did the Blacks at which John Henry supposedly fired his weapon originate? Neither the McKeys nor the Hollidays owned slaves at this time in Georgia, since it was the post-Civil War era, and no Blacks lived upon the McKey or Holliday properties. The combined acreage created a reasonably extensive tract of land with few if any neighbors in what then was basically still an unsettled wilderness in south Georgia. So from whence did the manufactured Blacks come? No one has the answer. More speculation.

The time-line for the occurrence of this incident is faulty as well. A pre-February, 1872 swimming hole shooting incident in Valdosta must be ruled out, since Holiday’s uncles – William H. and Thomas S. McKey – did not even purchase their Withlacoochee River acreage until February of ‘72. And a date after that February is even more unlikely. The shooting (if such occurred) almost certainly had to have occurred prior to John Henry’s entry into the Pennsylvania School of Dental Surgery in Philadelphia, wherein he was preoccupied with his education and, immediately afterwards, the cultivation of his professional career.

John Henry was involved with his education at the Philadelphia school from 1870 to 1872 – much too far from home to be involved in swimming hole trivialities. From March thru October of 1871, the Georgian fulfilled the requirements for his eight-month dental preceptorship (apprenticeship) with Dr. Julian Frink. On November 6, 1871, Doc’s classes resumed in Philadelphia and continued until graduation in March of 1872.

Following the conclusion of his educational pursuits, John Henry immediately began the pursuit of his young professional life. On April 3, 1872, the Georgia State Dental Society opened its fifth annual convention in Atlanta, which Doc almost certainly attended to establish important contacts for his budding career. Though no written account of his actual presence at this event has been discovered, he, as a young and ambitious medical professional, would have been loathe to have missed this opportunity to rub shoulders with Georgia dental professionals.

Lest we forget, the sole aim of John Henry Holliday at this time in his young life was the pursuit of the profession in which he had invested so much time, energy and money. By this point, he had no thoughts whatsoever of idle playtime in a swimming hole in the wilds of south Georgia, much less of foolhardy gunplay with trespassing Negroes.

And what of the public records – the newspapers and court documents – which would have recorded a shooting of this nature? No such incident is mentioned anywhere in the Lowndes County news media nor court records. Why is that? Could it be due to the fact that the incident didn’t occur at all in Lowndes?

It also is quite possible that in 1872 or even in 1873, John Henry Holliday returned to his original boyhood home of “Griffin,” Georgia, to practice dentistry there for a short period of time after inheriting the “Iron Front Building,” a substantial commercial structure in the town. (Readers please see Chapter 5: “John Henry’s Last Georgia Possession” in this publication.) His mother had left the property to her son in her Will, and John Henry quite possibly briefly maintained a dental practice therein.

On April 3, 1873, the Georgia State Dental Society’s annual convention was held once again – this time in Columbus, Georgia. Dr. Arthur C. Ford was elected Society President, and he had already become significant in Holliday’s life, providing him with his first opportunity for a professional dental practice through a partnership. The Columbus Daily Sun published a list of all dentists practicing in the state prior to August 24, 1872. Listed among the 143 dentists was “Haliday, John H., Atlanta,” where he practiced in concert with Dr. Ford.

At some point around 1873 or shortly thereafter, John Henry Holliday became acquainted with the gambling trade and the debauchery so prevalent in the vicinity of his early employment with Dr. Ford. At some point, drinking, gambling, and womanizing took over his life and his professional dental practice “took a back seat.” He shortly became so dissolute that Dr. Ford apparently was compelled to sever his professional relationship with John Henry, sending Holliday’s life spiraling out of control and ultimately converting him into a vagabond traveling the West for adventure.

The combination of these circumstances left virtually no opportunity for the aforementioned “swimming hole incident” – as described by Mrs. Clyde McKey White and mimicked by William Barclay Masterson and Walter Noble Burns – in this portion of his life either, nor, in all likelihood, for it to have occurred in Valdosta at all. In point of fact, the most likely point at which something of this nature “might” have occurred would have been much earlier in Doc’s life at the Holliday family home in Griffin (not on the Withlacoochee in Valdosta), where a younger John Henry spent the first twelve years of his life.

Born in Griffin in 1851, John Henry lived for the first two years of his life in a small home on that town’s Tinsley Street. In October of 1853, Henry B. Holliday – Doc’s father – purchased a plantation one and one-half miles north of Griffin where the youngster spent the following ten years of his life. As stated, this property would have been a much more likely locale for a “swimming hole incident.” Even more telling, this property included a large natural spring (and associated popular swimming spot) at which a shooting incident quite easily could have occurred.

In March of 1862, Private Asbury H. Jackson (CSA infantry) sent a letter home to his mother from Griffin’s Confederate Camp Stephens. Included in this letter was a finely-drawn map which intricately detailed Camp Stephens, a substantial military training facility for the Confederacy. Mrs. Jackson and her heirs somehow had retained possession of the map down through time until it eventually was discovered in a dusty file drawer by an individual named Mike Watson in 2002.

Without Pvt. Jackson’s map, the specific location of Henry B. Holliday’s home – which had disappeared over the ensuing years – on his plantation might never have been known. Spalding County Deed Books A and B, provide a detailed description of the acreage included in the plantation, but no information regarding the Holliday home itself.

Despite Pvt. Jackson’s detailed map, the aforementioned plantation site – still wholly undeveloped right up to the 21st Century – had become completely obscured with the passage of years by dense undergrowth and forested expanses, causing any actual relocation of the former Holliday home to be extremely difficult. Even the ancient steel rails (which still exist to this day) from the historic Macon & Western Railroad had been completely hidden by all the heavy overgrowth of bushes, vines, scrub pines, and decayed vegetation. Nevertheless, after extensive research by Doc Holliday Society President Bill Dunn of Griffin and an associate, the foundation stones of the former Holliday home as well as the steel rails of the railroad were eventually uncovered and revealed.

Henry B. Holliday had initially purchased 147 acres in 1853 near Griffin situated north of the city proper and along the east side of what today is the long-abandoned Macon & Western Railroad tracks. Holliday subsequently sold 136 acres at this site to Confederate authorities for the creation of Confederate Camp Stephens and retained 11 acres for his home. He then purchased an additional 278 acres outside the bounds of Camp Stephens for a total of 289 acres in his plantation where he planted Sea Island cotton and corn. Henry Holliday’s 289-acre plantation was then bounded on the west by the Macon & Western Railroad, and on the east by Camp Stephens.

“Holliday Creek” which rises from the large natural spring on Henry’s property, almost certainly was the site of the much-debated “incident” – again, if it ever occurred at all – although it would, by virtue of the time-period – have involved a much younger John Henry Holliday who could not have been more than 12 years of age at the time.

According to Bat Masterson’s 1907 Human Life article on the swimming hole incident, “The Negro boys were informed that in the future, they would have to go further down the ‘stream’ to do their swimming, which they promptly refused to do, telling the Whites that if they didn’t like existing conditions, that they would have to hunt up a new swimming hole.” Defiance of this nature from Black slaves in 1860s Confederate Georgia – particularly as involved someone else’s private property – would have been highly unlikely, which, again, makes the occurrence of this presumed incident suspect at best – but it, nevertheless, made a good story.

If this incident in fact did occur, there were a number of different scenarios which might have transpired. At the top of the list would have to be the possible altercation between John Henry Holliday and the aforementioned Blacks. The “swimming hole,” however, was located on Holliday property, so if this did occur, young John Henry would have been well within his rights to order any trespassers from his father’s property. And if said trespassers threatened the youngster, he would have been well within his rights to fire warning shots to ward them off, particularly in Confederate Georgia.

Scenario number two would involve a group of Whites trespassing at the swimming hole who likewise refused to depart the Holliday property and who likewise were warded off with warning shots. There was at least one White family – that of William and Lucinda Bates – who lived on property directly across the railroad tracks from the Holliday tract who had male children of ages 17 and 19, as well as two other males of ages 12 and 14 in the household, all of whom would have been of the “bully” age at this time, and no doubt often patronizing the swimming hole. John Henry, once again, would have been well within his rights to demand their departure from the spot if this formed the basis of the scenario. It, however, would not include the racial component, so it no doubt would have gone with little mention beyond the actual occurrence of the incident.

And finally, if this incident ever occurred at all (because as detailed above, the original reference sources used by those describing this presumed incident were, at best, highly suspect or nonexistent), it most certainly did not involve any deaths or injuries, since no mention is made of any such injuries or deaths in either the newspapers or court records of either Lowndes or Spalding counties or the towns of Valdosta or Griffin, and John Henry – if involved at all – almost certainly would have been more than justified in his actions in that day and time anyway.

Also as explained above, all of this also would have been occurring with a John Henry Holliday who was not more than 12 years of age, since the Holliday family only resided in Griffin for the initial twelve years of John Henry’s life, so he would have been barely more than a youngster at the time anyway, even though he quite likely would have been well-versed in the use of firearms by age 12.

These things being said, the “swimming hole incident” and its highly-publicized racial component quite likely did not occur at all, and even if it did, John Henry Holliday would have been well within his rights for being involved in such an incident, and little more than a youngster to boot. It would therefore appear that this presumed incident was, in all likelihood, nothing more than a sensationalized incident fabricated around a non-existent racial component.

The Atlanta Dental Practice

Much of Atlanta’s former Whitehall Street is today named Peachtree Street (since it, in fairness, is basically the south end of that famed avenue). The building at the southeast corner of Alabama and Whitehall/Peachtree streets is not the one which once housed the dental offices of doctors Ford and Holliday, but it is the site at which John Henry “Doc” Holliday set up his first “recorded” dental practice in Georgia.

In Doc’s day, Peachtree Street ended and Whitehall Street began at the east-west juncture of the Macon & Western Railroad at this site (which interestingly is the same railroad which passed through his father’s property at John Henry’s boyhood home in Griffin, Georgia). “Railroad Gulch” still exists at this site in Atlanta today, but it is covered over and virtually obscured on the east side by viaducts and bridges which hide much of the rail yard which was so visibly portrayed in the epic and major motion picture Gone With the Wind.

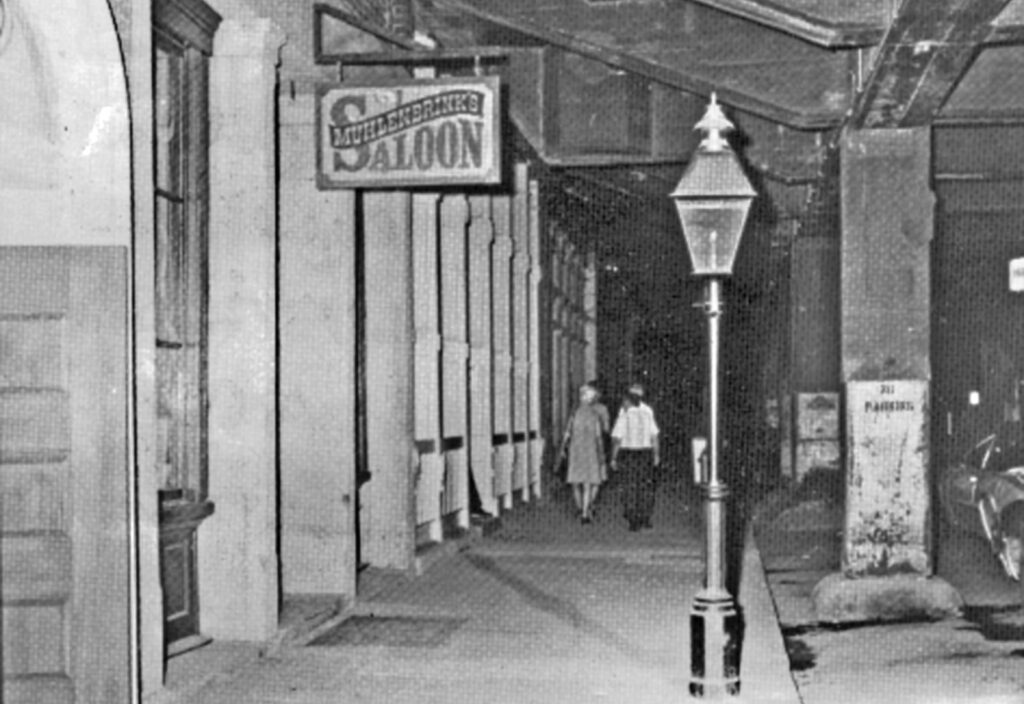

Unbeknownst to many, remnants of the former site of Holliday’s practice were still extant in the former popular 1960s and ‘70s entertainment complex once known as Underground Atlanta. Cobblestoned portions of Alabama and Whitehall streets still exist there beneath the viaducts even today, as do the lower level/basement sections once comprising some of Atlanta’s original commercial buildings.

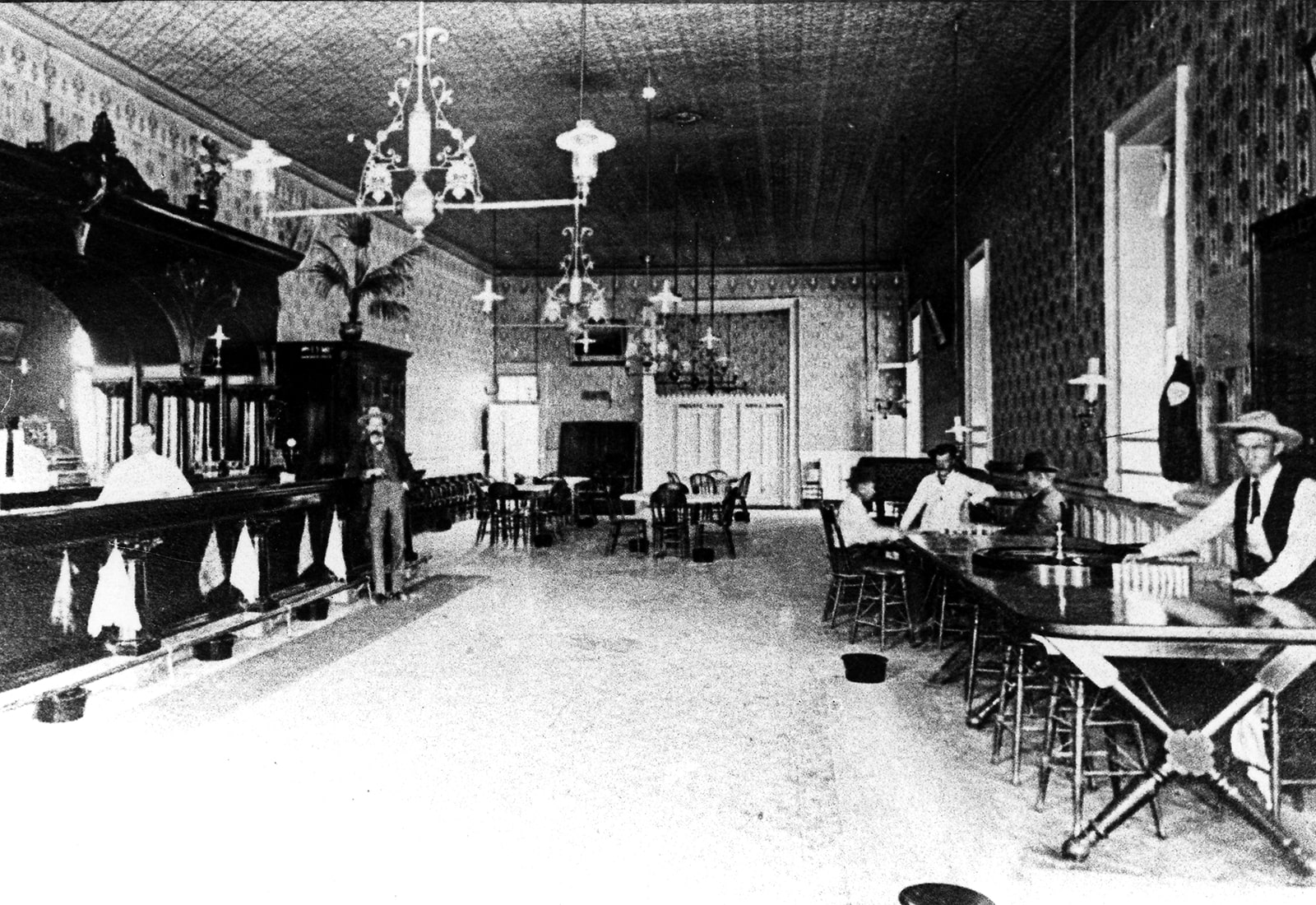

In Doc’s day (1870s), the Whitehall Street district formed the “Deadline” section of town “on the south side of the tracks.” Saloons and bordellos proliferated there, and, in a short period of time, these came to be heavily patronized by John Henry. The legend of the “Doc Holliday” known in Western lore was born and bred in this neighborhood. Did his eventual debauched behavior in Atlanta begin after his discovery of the fatal disease he carried in his lungs? Possibly. Likely.

The Hanleiter City Directory for the year 1870 lists a total of twenty saloons and bars in Atlanta. Fourteen of the twenty are clustered in the blocks just south of the railroad on Alabama, Hunter (present-day Martin Luther King Street), Mitchell, Broad, and Whitehall Streets. The fourteen saloons are: ME. Kenny, T.F. Grady, Dan Fleck, G. Hentschel, N.M. Robinson, Steadman and Kreis, J.L. Griffin, H. Muhlenbrink, M.E. Maher, D. Wallace, Michael Haverty, Frantz Eddleman, John Gaven, and Jake Emmel. “Muhlenbrink’s Saloon” was one of the storefronts which survived beneath the viaducts and which was later renovated and reused in the Underground Atlanta complex. This structure, quite possibly frequented by John Henry, likely still exists there even today.

In the years 1870 to 1874 (excluding 1873 for which there was no listing), a grand total of forty-six saloons operated south of Railroad Gulch. The bulk of Atlanta’s non-Whitehall Street saloons listed in Hanleiter’s were located in the mid-town district just north of the railroad.

The exact time that the dissolution from drink, gambling, and womanizing took possession of John Henry’s life is unknown today (yet another gap in his history), but it quite probably is fair to say it began with the severance of his professional partnership with Dr. Arthur C. Ford. At some point no more than a year after the initiation of their promising dental practice, Dr. Ford decided that he had erred in the assumption of a business relationship with his young protégé, sending John Henry Holliday adrift into the unknown.

After alcoholism took over his life, John Henry apparently pursued the lure of the gambling tables to an even greater extent, until his depravities had robbed him of any financial security he might have previously enjoyed. At this point, his inheritance of the Iron Front Building in Griffin from his late mother became a much-needed sudden windfall which allowed him to continue without a steady job.

As explained above, he apparently made a brief attempt at resuming a professional dental career in Griffin, but it was short-lived. The incident or incidents which had culminated in the termination of his relationship with Dr. Ford apparently had poisoned any further hope for employment in Atlanta or environs. After, all, no one wished to go into partnership with a drunken ne’er-do-well, nor did patients wish to have their teeth pulled or cavities drilled out by such a dentist.

As a result, at some point, John Henry Holliday was forced to face the conclusion that Atlanta and Georgia held little to no further allure for him. Realizing that he needed to depart for a site where he might “begin anew,” he set out for Texas, eventually winding up in Dallas.

Did this departure from Georgia coincide with his debauched behavior and the ruination of his professional career opportunities in Georgia; or was it the result of a tortured romance with his cousin Martha Anne “Mattie” Holliday; or was it in fact the diagnosis of his contraction of the terrible incurable disease known as tuberculosis which spurred his travel westward? We’ll never know, because he kept few if any letters or records on matters of this nature, and the reason or reasons for his relocation to the West became yet another gap in the collective record of the life of John Henry Holliday.

Cousin Mattie Holliday

Much has been made down through history of the reason or reasons for the departure of famed Western gunman John Henry “Doc” Holliday from Georgia. Was it due to a dissolution of his professional career as a result of an addiction to liquor and the gambling dens of Atlanta? Or was it due to a “swimming hole incident” in which he supposedly had maimed or killed one or more arrogant Negroes? Or was it due to a star-crossed romance with a cousin which sent her into a Convent for the remainder of her life and him into banishment from his home state of Georgia for the remainder of his life? Also as explained above, the simple answer to this is: We’ll never know.

Mattie Anne Holliday, the daughter of John Henry’s uncle – Robert K. Holliday – was Doc’s soulmate and playmate in the early years of his life, and his confidant until the day he died on a cold winter day in Glenwood Springs, Colorado in 1887. She was the one to whom he told his secrets, and the one with whom he formed a bond which endured for the remainder of both of their lives.

How deep was this relationship? The blessed few inklings offered by John Henry during his lifetime revealed nothing more than an unbreakable bond strongly akin to – if not the actual condition of – deep and affectionate love.

John Henry talked of her sparingly to others during his lifetime, but from the scant comments he did make, it was clear that she was extremely important to his life and that he deeply regretted the fact that they had been separated for life.

Unbeknownst by many, John Henry and Mattie (or “Sister Melanie” as she became known after making a life-time commitment to a Convent) communicated often by letter. And Mattie saved all of these letters, right up until the time of her death when, per her final instructions, the letters were burned. Regret at this action was later expressed with the statement, “Had the letters from John been retained, the world would have known a much different man from that described in books and magazine articles.”

So what happened? What caused Mattie to commit her life to a Catholic Convent and him to commit his life to that of an alcoholic gambler drifting across the Old West? We’ll likely never know the answer to those questions either. Still more gaps in the collective history of John Henry “Doc” Holliday.

Actual Site of His Grave

Also contrary to popular myth and modern movie portrayals, Doc Holliday did not die in the Glenwood Springs “Sanitarium.” There was no sanitarium in Glenwood Springs in 1887. Doc Holliday died in his room in the Hotel Glenwood.

Mystery seems to follow Doc right into the grave. The actual site of his burial is not known today either. There is a Doc Holliday gravesite in Linwood Cemetery outside Glenwood Springs, but it is an acknowledged fact that many historians believe Doc Holliday is not buried there. Even the cemetery records state only that it is believed that he is “buried somewhere in this cemetery.”

On the day of Doc’s funeral, the weather reportedly was bitterly cold. Along with John Henry, one other recently-deceased gentleman was to be buried in Linwood Cemetery on the same day. On the day of the burials, the trail up to the cemetery was completely impassable, and, as a result, Doc and the other deceased individual reportedly were buried by the side of the road “somewhere along the route up to the cemetery,” the intention being that they would be exhumed in the spring and re-buried within the actual cemetery.

The following spring, however, things changed a bit. The individual buried beside Doc apparently had family in the Glenwood Springs area who readily paid to have their loved one dug up and re-buried in Linwood. Doc, however, had no family in the area, and according to reports, no one was forthcoming to pay the fee to have him exhumed and re-buried. He, therefore, according to most reports, was left buried beside the road.

As time passed, local residents came and went and the actual site of the grave of famed John Henry Holliday supposedly and surprisingly was forgotten. It was only in the mid- to late-20th century that local residents – realizing the historic and tourism-related value of Doc’s burial site – began trying to re-locate his grave.

Despite considerable efforts toward this attempted relocation, the positive identification of John Henry’s gravesite has completely eluded researchers and historians. Today, the mortal remains of Dr. John Henry Holliday from Griffin and Valdosta, Georgia, possibly exist beneath someone’s back porch or in someone’s yard on the route up to Linwood Cemetery.

Other accounts, however, differ with the above scenario. According to one, Doc’s remains were indeed later dug up and re-buried in Linwood Cemetery, where they exist today. Another account maintains that they were dug up, but were transported – via the new railroad in Glenwood Springs – back to Georgia in the late 1880s, where they were re-buried in an unmarked grave in Griffin, Doc’s birthplace. If the remains in the unmarked grave in Griffin are excavated and examined via DNA analysis and for a tubercular condition, a connection to John Henry might be finally established. Time will tell.